Creating a PageRank algorithm with NumPy

If you’re using this post to find answers for your own PageRank, I strongly encourage you to fiddle around with your code more to see if you can get it to work. If you absolutely can’t figure it out, don’t just copy the code here, but find out why the code below works compared to what you had written.

Reflection: I found this mini-model of a PageRank algorithm to wonderfully combine key aspects of eigenvectors/eigenvalues, normalization, and the damping effect within a real-world application. Though, I’ve felt that the Python code isn’t explained very well in this assignment so I have made some annotations that will hopefully help to understand it if you are very new to python like myself. I have always imagined Google’s PageRank system as a web-crawler from a class I took in high school that explained it in that way, and by finding out how it works by making it myself, it definitely reinforces that idea. In linear algebra it often helps to think about matrices and vectors within a 2 or 3 dimensional space. However, in this case, that idea is abstracted to apply to a more logical application where we work with a 2-D square matrix that represents the links to all other pages on our mini-internets.

Part 1 - Worksheet

The majority of this blog was written by instructors from the online coursera course “Mathematics for Machine Learning” from the Imperial College of London with slight changes and notes from me which make it easier to refer to for study.

Introduction PageRank (developed by Larry Page and Sergey Brin) revolutionized web search by generating a ranked list of web pages based on the underlying connectivity of the web. The PageRank algorithm is based on an ideal random web surfer who, when reaching a page, goes to the next page by clicking on a link. The surfer has equal probability of clicking any link on the page and, when reaching a page with no links, has equal probability of moving to any other page by typing in its URL. In addition, the surfer may occasionally choose to type in a random URL instead of following the links on a page. The PageRank is the ranked order of the pages from the most to the least probable page the surfer will be viewing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Before we begin, let's load the libraries.

%pylab notebook

import numpy as np

import numpy.linalg as la

from readonly.PageRankFunctions import *

np.set_printoptions(suppress=True)

What does each line of this python code mean?

This Python code snippet is set up for numerical and scientific computing, particularly for tasks related to linear algebra, which is often used in fields like physics, engineering, and data science. Here’s what each line of the code does and an explanation of NumPy:

%pylab notebook

%pylab is a function in IPython that loads NumPy and Matplotlib into the current namespace, providing a MATLAB-like interactive environment. The notebook option allows these interactive features to be used within a Jupyter notebook, enabling inline plotting and other interactive features.

import numpy as np

This line imports the NumPy library and renames it as np. NumPy is a fundamental package for scientific computing in Python. It provides support for large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices, along with a collection of mathematical functions to operate on these arrays.

import numpy.linalg as la

This imports the linear algebra module (linalg) from NumPy and renames it as la. This module provides a range of functions for matrix operations, including solving equations, finding eigenvalues, and matrix decompositions, among other things.

from readonly.PageRankFunctions import *

This line imports all functions from the module PageRankFunctions located in a readonly directory. The exact functions aren’t specified, but based on the name, it’s likely that these are functions related to calculating or analyzing PageRank, which is an algorithm used by Google Search to rank web pages in their search engine results.

np.set_printoptions(suppress=True)

This sets the print options for NumPy. The suppress=True option means that very small floating-point numbers will be suppressed, which typically means they’ll be displayed as zero instead of using scientific notation. This makes the output more readable, especially when dealing with very small numbers in matrices or arrays.

Ok, but what even is NumPy?

NumPy (Numerical Python) is an open-source Python library that’s the foundational package for scientific computing in Python. It provides support for large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices, along with a large collection of high-level mathematical functions to operate on these arrays. It’s known for its high performance, ease of use, and interoperability with other libraries and programming languages. It’s widely used in academic and industrial settings, particularly for data analysis, machine learning, engineering, and scientific research.

PageRank as a linear algebra problem

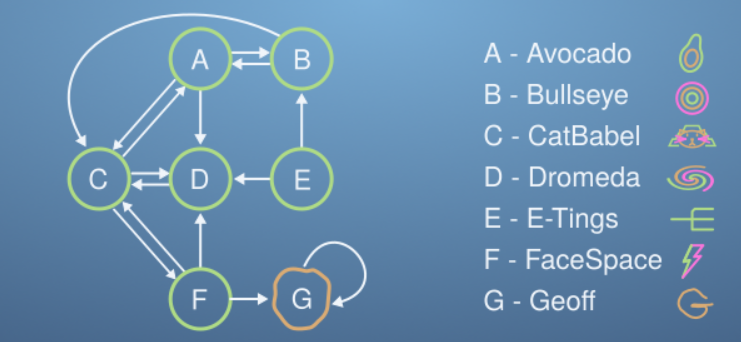

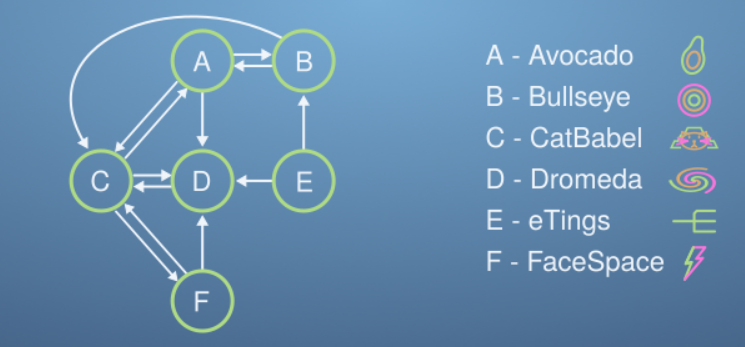

Let’s imagine a micro-internet, with just 6 websites (Avocado, Bullseye, CatBabel, Dromeda, eTings, and FaceSpace). Each website links to some of the others, and this forms a network as shown,

The design principle of PageRank is that important websites will be linked to by important websites. This somewhat recursive principle will form the basis of our thinking.

Imagine we have 100 Procrastinating Pats on our micro-internet, each viewing a single website at a time. Each minute the Pats follow a link on their website to another site on the micro-internet. After a while, the websites that are most linked to will have more Pats visiting them, and in the long run, each minute for every Pat that leaves a website, another will enter keeping the total numbers of Pats on each website constant. The PageRank is simply the ranking of websites by how many Pats they have on them at the end of this process.

We represent the number of Pats on each website with the vector, r = [rA, rB, rC, rD, rE, rF]

And say that the number of Pats on each website in minute (i+1) is related to those at minute (i) by the matrix transformation

r^(i+1) = Lr(i)

with the matrix L taking the form,

| L_A→A, L_B→A, L_C→A, L_D→A, L_E→A, L_F→A |

| L_A→B, L_B→B, L_C→B, L_D→B, L_E→B, L_F→B |

| L_A→C, L_B→C, L_C→C, L_D→C, L_E→C, L_F→C |

| L_A→D, L_B→D, L_C→D, L_D→D, L_E→D, L_F→D |

| L_A→E, L_B→E, L_C→E, L_D→E, L_E→E, L_F→E |

| L_A→F, L_B→F, L_C→F, L_D→F, L_E→F, L_F→F |

where the columns represent the probability of leaving a website for any other website, and sum to one. The rows determine how likely you are to enter a website from any other, though these need not add to one. The long time behaviour of this system is when the vector r at iteration i+1 is equal to the matrix L multiplied by the vector at iteration i so we’ll drop the superscripts here, and that allows us to write,

Complete the matrix L below, we’ve left out the column for which websites the FaceSpace website (F) links to. Remember, this is the probability to click on another website from this one, so each column should add to one (by scaling by the number of links).

1

2

3

4

5

6

L = np.array([[0, 1/2, 1/3, 0, 0, 0 ],

[1/3, 0, 0, 0, 1/2, 0 ],

[1/3, 1/2, 0, 1, 0, 1/2 ],

[1/3, 0, 1/3, 0, 1/2, 1/2 ],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ],

[0, 0, 1/3, 0, 0, 0 ]])

In principle, we could use a linear algebra library, as below, to calculate the eigenvalues and vectors. And this would work for a small system. But this gets unmanageable for large systems. And since we only care about the principal eigenvector (the one with the largest eigenvalue, which will be 1 in this case), we can use the power iteration method which will scale better, and is faster for large systems. The code below demonstrates the PageRank for this micro-internet.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

eVals, eVecs = la.eig(L) # Gets the eigenvalues (eVals) and vectors (eVecs)

#This line calculates the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix L using NumPy's linear algebra module (numpy.linalg, aliased as la).

order = np.absolute(eVals).argsort()[::-1] # Sorts the indices of the eigenvalues by their magnitude in descending order

eVals = eVals[order] #reorders the eigenvalues so the largest (absolute value) is first

eVecs = eVecs[:,order] #reorders the columns of the eigenvector matrix correspondingly

r = eVecs[:, 0] # Sets r to be the principal eigenvector

100 * np.real(r / np.sum(r))

# Normalizes this eigenvector sum to one, then multiplied by 100 Procrastinating Pats to represent percentages

Output:

array([ 16. , 5.33333333, 40. , 25.33333333, 0. , 13.33333333])

We can see from this list, the number of Procrastinating Pats that we expect to find on each website after long times. Putting them in order of popularity (based on this metric), the PageRank of this micro-internet is:

CatBabel, Dromeda, Avocado, FaceSpace, Bullseye, eTings

Referring back to the micro-internet diagram, is this what you would have expected?

Convince yourself that based on which pages seem important given which others link to them, that this is a sensible ranking. Let’s now try to get the same result using the Power-Iteration method that was covered in the video. This method will be much better at dealing with large systems.

First let’s set up our initial vector, r^(0), so that we have our 100 Procrastinating Pats equally distributed on each of our 6 websites.

1

2

r = 100 * np.ones(6) / 6 # Sets up this vector (6 entries of 1/6 × 100 each)

r # Shows it's value

Output:

array([16.66666667, 16.66666667, 16.66666667, 16.66666667, 16.66666667, 16.66666667])

Next, let’s update the vector to the next minute, with the matrix L. Run the following cell multiple times, until the answer stabilizes.

1

2

r = L @ r # Apply matrix L to r

r # Show it's value

We need to re-run this cell multiple times to converge to the correct answer which we can automate with the following code which applies the matrix 100x with a for-loop

1

2

3

4

r = 100 * np.ones(6) / 6 # Sets up this vector (6 entries of 1/6 × 100 each)

for i in np.arange(100) : # Repeat 100 times

r = L @ r

r

Output: array([ 16. , 5.33333333, 40. , 25.33333333, 0. , 13.33333333])

Or even better, we can keep running until we get to the required tolerance, in this case, we will set it to a 0.01 difference from the previous iteration.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

r = 100 * np.ones(6) / 6 # Sets up this vector (6 entries of 1/6 × 100 each)

lastR = r

r = L @ r

i = 0

while la.norm(lastR - r) > 0.01 :

lastR = r

r = L @ r

i += 1

print(str(i) + " iterations to convergence.")

r

Output: 18 iterations to convergence. array([ 16.00149917, 5.33252025, 39.99916911, 25.3324738 , 0. , 13.33433767])

See how the PageRank order is established fairly quickly, and the vector converges on the value we calculated earlier after a few tens of repeats. Congratulations! You’ve just calculated your first PageRank!

Damping Parameter

The system we just studied converged fairly quickly to the correct answer. Let’s consider an extension to our micro-internet where things start to go wrong.

Say a new website is added to the micro-internet: Geoff’s Website. This website is linked to by FaceSpace and only links to itself.

Intuitively, only FaceSpace, which is in the bottom half of the page rank, links to this website amongst the two others it links to, so we might expect Geoff’s site to have a correspondingly low PageRank score. Build the new L matrix for the expanded micro-internet, and use Power-Iteration on the Procrastinating Pat vector. See what happens…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# We'll call this one L2, to distinguish it from the previous L.

L2 = np.array([[0, 1/2, 1/3, 0, 0, 0, 0 ],

[1/3, 0, 0, 0, 1/2, 0, 0 ],

[1/3, 1/2, 0, 1, 0, 1/3, 0 ],

[1/3, 0, 1/3, 0, 1/2, 1/3, 0 ],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ],

[0, 0, 1/3, 0, 0, 0, 0 ],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1/3, 1 ]])

r = 100 * np.ones(7) / 7 # Sets up this vector (6 entries of 1/6 × 100 each)

lastR = r

r = L2 @ r

i = 0

while la.norm(lastR - r) > 0.01 :

lastR = r

r = L2 @ r

i += 1

print(str(i) + " iterations to convergence.")

r

Output: 131 iterations to convergence.

array([ 0.03046998, 0.01064323, 0.07126612, 0.04423198, 0. , 0.02489342, 99.81849527])

That’s no good! Geoff seems to be taking all the traffic on the micro-internet, and somehow coming at the top of the PageRank. This behaviour can be understood, because once a Pat get’s to Geoff’s Website, they can’t leave, as all links head back to Geoff.

To address this issue, we can introduce a small probability that the Procrastinating Pats don’t follow any link on a webpage, but instead visit a random website on the micro-internet. Let’s say the probability of them following a link is 𝑑, and the probability of choosing a random website is therefore 1−𝑑

We can use a new matrix to determine where the Pats visit each minute:

M=d⋅L+(1−d)/n)⋅J

Here, J is an 𝑛×𝑛 matrix where every element is one.

- If 𝑑 is one, it means we have the same situation as before, where the Pats always follow the links.

- If 𝑑 is zero, the Pats will always visit a random webpage, making all webpages equally likely to be visited and equally ranked.

For this method to be most effective, 1−𝑑 should be relatively small. However, we won’t go into the details of exactly how small it should be.

Let’s retry this PageRank with this extension.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

d = 0.5 # Feel free to play with this parameter after running the code once.

M = d * L2 + (1-d)/7 * np.ones([7, 7]) # np.ones() is the J matrix, with ones for each entry.

r = 100 * np.ones(7) / 7 # Sets up this vector (7 entries of 1/7 × 100 each)

lastR = r

r = M @ r

i = 0

while la.norm(lastR - r) > 0.01 :

lastR = r

r = M @ r

i += 1

print(str(i) + " iterations to convergence.")

r

This is certainly better, the PageRank gives sensible numbers for the Procrastinating Pats that end up on each webpage. This method still predicts Geoff has a high ranking webpage however. This could be seen as a consequence of using a small network. We could also get around the problem by not counting self-links when producing the L matrix (an if a website has no outgoing links, make it link to all websites equally). We won’t look further down this route, as this is in the realm of improvements to PageRank, rather than eigenproblems.

You are now in a good position, having gained an understanding of PageRank, to produce your own code to calculate the PageRank of a website with thousands of entries.

Good Luck!

Part 2 - Assessment

In this assessment, you will be asked to produce a function that can calculate the PageRank for an arbitrarily large probability matrix. This, the final assignment of the course, will give less guidance than previous assessments. You will be expected to utilize code from earlier in the worksheet and repurpose it to your needs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

# PACKAGE

# Here are the imports again, just in case you need them.

# There is no need to edit or submit this cell.

import numpy as np

import numpy.linalg as la

from readonly.PageRankFunctions import *

np.set_printoptions(suppress=True)

# GRADED FUNCTION

# Complete this function to provide the PageRank for an arbitrarily sized internet.

# I.e. the principal eigenvector of the damped system, using the power iteration method.

# (Normalisation doesn't matter here)

# The functions inputs are the linkMatrix, and d, the damping parameter - as defined in this worksheet.

# (The damping parameter, d, will be set by the function - no need to set this yourself.)

def pageRank(linkMatrix, d) :

n = linkMatrix.shape[0]

r = 100 * np.ones(n) / n # Start with an equal probability for each page

M = d * linkMatrix + (1-d)/n * np.ones([n, n]) #m = damping

#keep running until we get to the required tolerance of <= 0.01

lastR = r

r = M @ r

i = 0

while la.norm(lastR - r) > 0.01 :

lastR = r

r = M @ r

i += 1

print(str(i) + " iterations to convergence.")

return r

Testing the code:

1

2

L = generate_internet(10) #This generates internets of a specified size

pageRank(L, 1)

Output example:

13 iterations to convergence.

array([ 44.11048081, 0.0000165 , 23.5293713 , 0.00703436, 0.00006938, 0.00008899, 0.0000165 , 20.58819215, 11.7646939 , 0.00003611])

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

#Adding the damping factor:

d = 0.85

# Create the damping matrix

E = np.ones(L.shape) / L.shape[0]

# Damp the link matrix

M = d*L + ((1-d) / L.shape[0]) * E

# Calculate eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the damped matrix

eVals, eVecs = la.eig(M)

order = np.absolute(eVals).argsort()[::-1]

eVals = eVals[order]

eVecs = eVecs[:,order]

# Extract the principal eigenvector

r = eVecs[:, 0]

# Normalize to percentage

r = 100 * np.real(r / np.sum(r))

# You may wish to view the PageRank graphically.

# This code will draw a bar chart, for each (numbered) website on the generated internet,

# The height of each bar will be the score in the PageRank.

# Run this code to see the PageRank for each internet you generate.

# Hopefully you should see what you might expect

# - there are a few clusters of important websites, but most on the internet are rubbish!

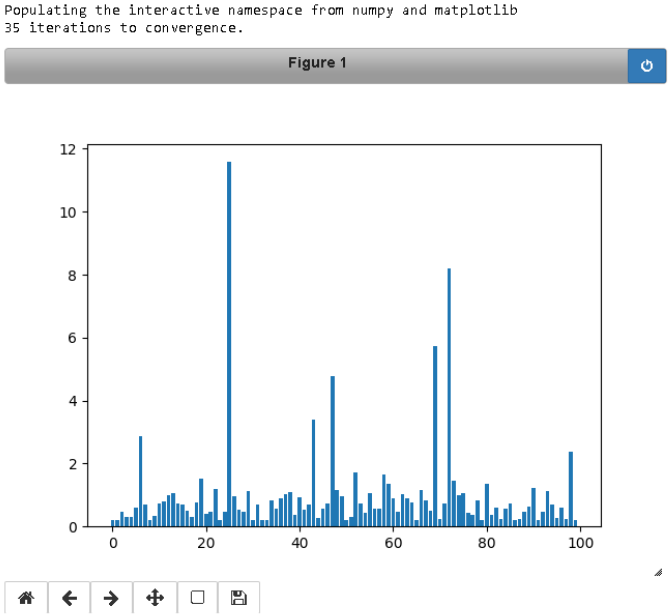

%pylab notebook

r = pageRank(generate_internet(100), 0.9)

plt.bar(arange(r.shape[0]), r);

Sample Output: